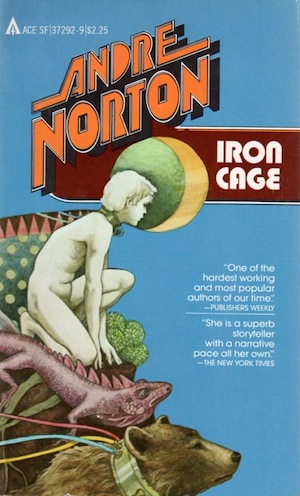

Iron Cage is one of the darker Norton novels. It’s set in a universe that consists exclusively of people who treat other sentient beings as things to be used and abused, experimented on and thrown away, and the victims of these abusers. The purpose is explicitly didactic: prologue and epilogue tell the story of a pregnant mother cat locked in a cage and literally thrown away even while she has her kittens.

Within the frame, we’re told the story of Rutee, a human woman kept in a cage on an alien starship. She and her husband were colonists on a newly discovered world, and were captured and taken offworld to serve as mind-controlled slaves.

But Rutee and Bron could not be controlled, and their young son Jony has turned out to be even less susceptible to the aliens’ devices. Bron has been disposed of. Rutee was forcibly bred to one of the controlled humans, and the twin offspring did not inherit Rutee’s resistance.

In the first few pages therefore, we have a whole slew of triggers, from animal abuse to slavery to mind control to rape. Then through a combination of lucky chances and sheer determination, Rutee manages to overpower her captors and free her children, and they escape onto an alien but habitable planet.

The planet has a usual-for-Norton population of dangerous monsters including mobile and carnivorous plants. It also has a species of large, bearlike sentients who live in clan groups. Their culture is very low-tech, and their language is not accessible to human vocal apparatus or, it seems, human frames of reference. But they take in the humans, feed and care for them, and communicate through sign language and a few vocalizations, mostly names.

As usually happens to mothers in Norton novels, Rutee is weak and frail and eventually dies, but not before she teaches Jony and the twins everything she can about human language and culture and the colony from which she and Bron were abducted. Jony is then left to look after the twins, with whom he feels little connection. They can’t read and control minds as he can (though Rutee made him solemnly swear not to control anyone ever), and he can’t forgive them for being the offspring of a rapist, even though he did it under alien compulsion.

The story proper gets underway when Jony sneaks off to explore a place the People shun, a network of paved roads leading to a mysterious ruined city. There he finds unimaginably ancient evidence of humanoid inhabitants. When he goes back to the People’s camp, he finds that the twins have disappeared.

They followed him to the city and discovered a trove of treasures including a man in suspended animation and a weapon that vaporizes whatever it’s aimed at. He rescues the twins, but when he returns to the People, he suffers severe consequences. They remember how their ancestors were put in control collars by humans and kept in cages like animals. They are now convinced that Jony is going to do the same, and will not allow him to defend himself. Instead they put one of the collars on him and lead him on a leash away from the city.

Buy the Book

Sun-Daughters, Sea-Daughters

Jony has already been caged by spacefaring aliens. Now he’s treated in a similar way by the aliens who cared for and raised him. It’s a tremendous betrayal, but he understands it. The People have strong reasons for their loss of trust.

After he manages to escape, but with the intention of freeing himself from the collar and proving to the People that he’s not the monster they think he is, a new complication bursts onto the scene. A rocket ship comes screaming in. Jony is sure it’s the Big Ones returning to put him back in the cage, but instead it’s human scouts claiming the planet for colonization. They quickly capture the twins and four of the People, and Jony has to break into the ship and set them free.

To do this, Jony uses mind control in spite of his promise to Rutee. But the humans know about mind powers, and have means to block it. They also have their own form of mind control, which turns the boy twin, Geogee, against his sister and his half-brother and the People. The girl twin, Maba, comes back around to Jony’s way of thinking and does her best to help free the People, but Geogee is all in for the other side.

In the end, Jony and Maba and the People rush to the city to rescue Geogee and try to stop the humans from getting hold of the ancient weapons. Jony keeps right on using mind control—he has to, he tells himself: there’s no other way to save the planet and the People. Eventually he destroys both the artifacts and the humans’ ship, and maroons the invaders. Too bad for them, he thinks, but the People won’t ever be collared or caged again, and he’s on their side to the end. He knows what it’s like to be caged, too.

It is, as I said, odd and dark and triggery. The People never really connect with Jony, and he’s completely alone for most of the book, even when he’s surrounded by humans and aliens. He has no friends and no one he loves, except his mother who died. All he really has is duty, responsibility, and mind powers that he’s not supposed to use to control people, but he keeps finding reasons to do it anyway.

We’re supposed to see the parallel with the way contemporary humans mistreat the mother cat, and to Learn a Lesson From It. Just as Jony rescues the People and makes the invaders pay for their crimes, in the epilogue, a warmhearted kid rescues the mother cat and her kittens. We’re supposed to treat animals well and think of them as fellow sentients, and not use them or experiment on them or turn them into slaves.

On the one hand I get that up close and personal. As I write this, there’s a rescue kitten asleep on my knee. She comes from a large colony on the other side of the valley, and they were rescued en masse—captured and caged, yes, but in order to move them into foster homes, give them veterinary care, and find permanent homes. So, yes, I get the lesson Norton is trying to teach, and I do my bit for animal rights on this planet.

On the other hand, this is not even close to my personal top tier of Norton novels. The pacing is rapid and the adventure is nonstop (and a large portion of it takes place underground in classic Norton fashion), and Jony has a far more extensive inner life than most Norton protagonists. Maba starts off being severely one-note—Annoying Screaming Child—but matures into a strong-willed and independent person, and that’s good. But the world they live in is kind of horrid, and the Lesson is a bit on the heavy-handed side. It’s not her best work, though to be fair, it’s not her worst, either.

Next I’ll move on to Breed to Come, which as I recall is a favorite of some of our regular commenters.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.